Chapare virus Explained: All about the rare Ebola-like virus that can spread from human to human.

What is the Chapare virus? What have CDC researchers discovered about the virus? How is the Chapare hemorrhagic fever treated? What is the threat posed by the Chapare virus?

A rare Ebola-like illness that is believed to have first originated in rural Bolivia in 2004 can spread through human-to-human transmission, researchers from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have discovered.

The biggest outbreak of the ‘Chapare virus’ was reported in 2019, when three healthcare workers contracted the illness from two patients in the Bolivian capital of La Paz. Two of the medical professionals and one patient later died. Prior to that, a single confirmed case of the disease and a small cluster were documented in the Chapare region over a decade ago.

While governments, scientists and health experts across the world struggle to contain a second wave of coronavirus outbreaks, researchers at the US’ CDC are now studying the virus to see if it could eventually pose a threat to humankind.

What is the Chapare virus?

What is the Chapare virus?

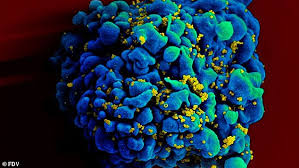

The Chapare hemorrhagic fever (CHHF) is caused by the same arenavirus family that is responsible for illnesses such as the Ebola virus disease (EVD). According to the CDC website, arenaviruses like the Chapare virus are generally carried by rats and can be transmitted through direct contact with the infected rodent, its urine and droppings, or through contact with an infected person.

The virus, which is named Chapare after the province in which it was first observed, causes a hemorrhagic fever much like Ebola along with abdominal pain, vomiting, bleeding gums, skin rash and pain behind the eyes. Viral hemorrhagic fevers are a severe and life-threatening kind of illness that can affect multiple organs and damage the walls of blood vessels.

However, not a lot is known about the mysterious Chapare virus. Scientists believe that the virus could have been circulating in Bolivia for many years, even before it was formally documented. Infected people may have been misdiagnosed with dengue as the mosquito-borne illness is known to cause similar symptoms.

What have CDC researchers discovered about the virus?

At the annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) earlier this week, researchers from the US’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that by examining the 2019 outbreak in Bolivia, they had found the virus can spread from person to person, particularly in healthcare settings.

“Our work confirmed that a young medical resident, an ambulance medic and a gastroenterologist all contracted the virus after encounters with infected patients — and two of these healthcare workers later died,” Caitlin Cossaboom, an epidemiologist with the CDC’s division of high-consequence pathogens and pathology said in a statement. “We now believe many bodily fluids can potentially carry the virus.”

The researchers said that based on the evidence available, healthcare workers are at higher risk of contracting the illness and must thus be extremely cautious while dealing with patients to avoid contact with items that could be contaminated with their blood, urine, saliva or semen.

They found that the medical resident who succumbed to the disease could have been infected while suctioning saliva from a patient. Meanwhile, the ambulance medic who contracted the illness but survived was likely to have been infected when he resuscitated the same medical resident while she was being transported to the hospital, according to the press release.

The researchers also found fragments of genetic entities known as RNA, associated with Chapare, in the semen of one survivor 168 days after he was infected. This suggests that the disease could also be sexually transmitted, they said.

The researchers also found fragments of genetic entities known as RNA, associated with Chapare, in the semen of one survivor 168 days after he was infected. This suggests that the disease could also be sexually transmitted, they said.

They also discovered signs of the virus in rodents in the “home and nearby farmlands” surrounding the first person infected during the 2019 outbreak, according to a report by Live Science.

“The genome sequence of the RNA we isolated in rodent specimens matches quite well with what we have seen in human cases,” Cossaboom said. The rodent species, in which Chapare viral RNA was identified, is commonly known as the pigmy rat and is found across Bolivia and in several of its neighbouring countries.

New sequencing tools will allow the CDC experts to quickly develop an RT-PCR test — much like the one used to diagnose Covid-19 — to help them detect Chapare. The researchers’ focus now is to identify how the disease is spreading across the country and whether rodents are in fact responsible for its spread.

How is the Chapare hemorrhagic fever treated?

Since there are no specific drugs to treat the disease, patients generally receive supportive care such as intravenous fluids.

The CDC website lists maintenance of hydration, management of shock through fluid resuscitation, sedation, pain relief and transfusions as the supportive therapy that can be administered on patients suffering from CHHF.

As there are very few cases on record, the mortality and risk factors associated with the illness are relatively unknown. “In the first known outbreak, the only confirmed case was fatal. In the second outbreak in 2019, three out of five documented cases were fatal (case-fatality rate of 60%),” an entry on the website points out.

What is the threat posed by the Chapare virus?

What is the threat posed by the Chapare virus?

Scientists have pointed out that the Chapare virus is much more difficult to catch than the coronavirus as it is not transmissible via the respiratory route. Instead, Chapare spreads only through direct contact with bodily fluids.

The people who are particularly at risk of contracting the illness are healthcare workers and family members who come in close contact with infected people. The disease is also known to be most commonly transmitted in more tropical regions, particularly in certain parts of South America where the small-eared pigmy rice rat is commonly found.

“This is not the sort of virus that we need to worry is going to start the next pandemic or create a major outbreak,” ASTMH scientific program chair and president-elect Daniel Bausch told Insider.